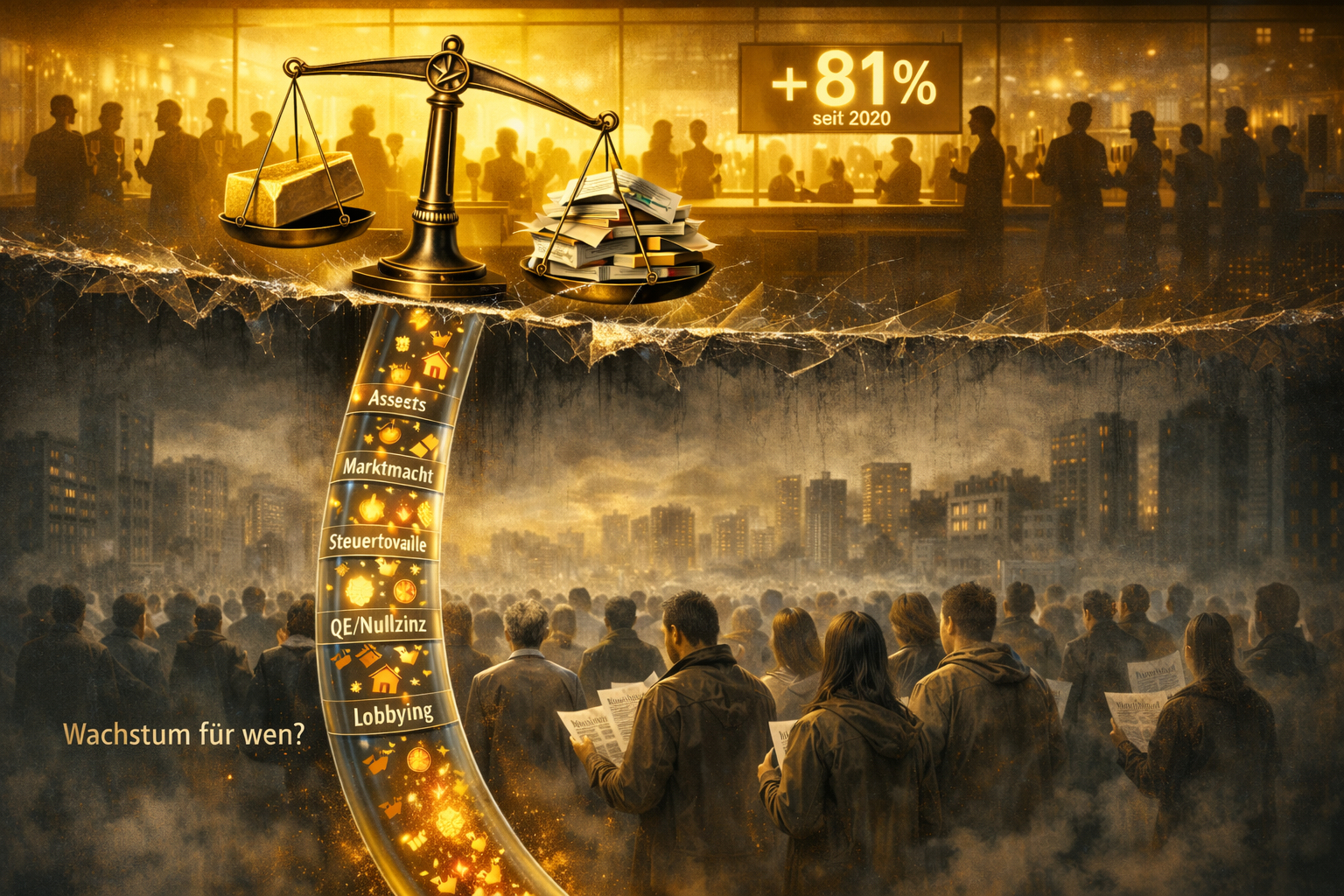

Imagine there were an economic system that, in crises, doesn’t tighten its belt but suddenly switches to “turbo” for the richest. That’s exactly how Oxfam’s new inequality finding reads: Since March 2020, the total wealth of billionaires has risen, adjusted for inflation, by 81% (or by 8.2 trillion US dollars). In 2025 alone, an additional +2.5 trillion US dollars were added; in total, billionaire wealth now stands at 18.3 trillion US dollars.

That sounds like a state of emergency – but is rather the end point of a 50‑year development in which money, power, and returns have gradually shifted upwards. The “81% since 2020” is not a bolt from the blue. It is the visible tip of a wave that has been building since the 1970s.

In this article, we place the current explosion of billionaire wealth in the long-term trend: What has structurally changed since the 1970s? Why is it accelerating right now? And which mechanisms turn wealth into a self-reinforcing system?

1) The Oxfam finding in one sentence – and why it is so explosive

Oxfam does not just describe wealth, but a combination of wealth growth and increasing political clout. The report emphasizes that billionaires extremely often attain political office and, through ownership of media and platforms, can influence public opinion.

And while this top segment grows, the same document contains a figure that hits like a moral punch: The poorer half of the world owns only 0.52% of global wealth, the richest 1% owns 43.8%.

This makes it clear: It’s not about “a few more rich people”, but about a structure in which the wealth pyramid is becoming increasingly pointed.

2) A 50-year look back: How we slipped into this “era of billionaires”

The 1970s: The end of the post-war logic

Up into the 1970s, the basic idea in many Western countries was: Growth should be broadly shared – through strong collective bargaining coverage, rising real wages, high top tax rates, and expansion of public infrastructure.

The breaking point is not “one date”, but a pattern: Since the late 1970s, a gap has opened between what the economy produces and what “typical” employees see from it as wage growth. The Economic Policy Institute shows very clearly for the USA the growing gap between productivity and typical hourly compensation since 1979.

Important: This is not just a U.S. phenomenon, but the U.S. is the most visible “laboratory” for the trend.

The 1980s: Tax and power shift (relief at the top, discipline at the bottom)

In many OECD countries, top tax rates fall significantly from the 1980s onward: An OECD analysis shows that the OECD‑wide average of top personal income tax rates fell over decades – from about 66% (1981) to 51% (1990) and further to 41% (2008).

At the same time, workers’ bargaining power crumbles: The OECD reports that union density has roughly halved since the mid‑1980s (from around 30% to about 15% in 2023/24).

In short:

Less countervailing power of labor + less redistribution through taxes = more room for returns and wealth accumulation at the top.

The 1990s: Globalization & tech – winners take more than “just their share”

The 1990s were shaped by market opening, outsourcing, financial and trade integration – and a tech surge. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) summarizes research to the effect that technological change is a central driver of rising inequality; trade can partly reduce inequality, while financial globalization tends to increase inequality.

This means: Even if global poverty falls in parts of the world through growth (e.g., in Asia), distribution within many countries can flip – and that is exactly what happens.

The 2000s: Financialization – wealth earns returns on wealth

By the 2000s at the latest, more and more prosperity is generated through assets: stocks, real estate, equity stakes, financial products. Those who own a lot benefit disproportionately.

And: Market power grows. An IMF working paper shows a strong increase in markups (as an indicator of market power) for advanced economies since 1980.

The 2010s: Zero interest rates, QE, asset boom – and the gap becomes a ramp

After the financial crisis, low interest rates and bond purchases (quantitative easing) dominate. The Bank of England openly explains: QE increases, among other things, the value of assets such as stocks – and thus increases the wealth of those who own these assets (with distributional effects).

Those who already own a lot are thus sitting in a return elevator.

The 2020s: Pandemic, market rally, AI boom – turbo for the top

And then comes 2020: crash, massive support programs, rapid stock market recovery, tech rally, later AI hype. Oxfam quantifies the result: +81% billionaire wealth since March 2020 and +16% in 2025 alone.

3) A brief reality check: “There have always been billionaires” – yes, but not like this

To grasp the scale: The modern, globally visible “billionaire economy” has a clear marker. In 1987, Forbes published its first international billionaire list – with 140 people.

Today, Oxfam says that the number of billionaires has risen above 3,000 for the first time.

This is not just “more prosperity”, this is a different system level.

4) The main reasons: Why billionaire wealth is rising so sharply

Here are the central drivers – not as a conspiracy, but as an economic mechanism that has intensified over decades:

Reason 1: Asset prices rise faster than wages (asset price channel)

Billionaire wealth is often tied to corporate equity. When stock markets, company valuations, and real estate prices rise, large fortunes grow automatically.

Central bank policy can amplify this effect: The Bank of England explicitly states that QE increases the value of assets such as stocks – and thus primarily benefits owners of such assets.

Translation: Those who are rich have a portfolio. Those who have a portfolio benefit disproportionately from asset booms.

Reason 2: Labor loses bargaining power – value creation shifts upward

When collective bargaining coverage, union power, and institutional protections weaken, the share of value creation shifts from wages to profits.

- OECD: Union density roughly halved since 1985.

- EPI: Productivity and typical compensation have been drifting apart since 1979.

This is not a moral argument, but a distribution logic: Less countervailing power → more room for profits → more wealth for shareholders.

Reason 3: Taxes have (on average) become more “top-friendly”

A large part of redistribution happens through taxes and transfers. When top tax rates fall, more remains at the top – and can be reinvested (compound interest effect).

The OECD shows that average top income tax rates have fallen sharply over decades.

(As an example of national time series, the Tax Policy Center provides historical U.S. top tax rates.)

Important: It’s not just about “how high”, but also about what is taxed how – labor vs. capital gains, inheritances, wealth.

Reason 4: Market power & monopoly dynamics increase profits (and thus wealth)

When companies have market power, they can enforce higher margins. This boosts profits – and in turn stock prices and owner wealth.

- IMF: Markups rose significantly in advanced economies since 1980.

- OECD: Markups also rose on average from 2000–2019; particularly strongly in digitally intensive industries.

Tech platforms in particular are predestined for “winner‑takes‑most”: network effects, data advantages, scaling. This is a billionaire generator.

Reason 5: Technology & financial globalization act as inequality amplifiers

The IMF emphasizes in a summary of research that technological progress has contributed significantly to rising inequality. At the same time, financial globalization tends to increase inequality.

Mechanically, this means:

- Tech rewards certain skills, economies of scale, and capital ownership.

- Financial globalization facilitates capital mobility, tax optimization, and yield seeking.

Reason 6: Inheritances stabilize wealth across generations

When wealth is large enough, it is no longer “earned” but managed and inherited. The OECD currently has its own analysis on inheritance taxation (with a view to inequality and reform options).

This is important because it makes wealth less dependent on performance and more dependent on starting position.

Reason 7: The “gain of the top 10%” is the “loss of the bottom 50%” – empirically visible

A drastic but well-documented finding from inequality research: Since 1995, a very large share of global wealth growth has gone to the top. A World Bank document that draws on results from the World Inequality Report describes, for example, that the bottom half received only a very small share of global wealth growth, while the top 1% received a large share.

And this corresponds to regional wealth shares: The World Inequality Report shows that the richest 1% own about a quarter (Europe) to 35–46% (North and Latin America) of total wealth, depending on the region.

5) Why the jump since 2020 is so extreme: Three accelerators

Accelerator A: Crisis policy + asset rally

The pandemic was an economic shock – but stock markets and valuations recovered quickly in many countries. Those heavily invested in assets benefit disproportionately in a recovery rally.

Oxfam makes this dynamic tangible in numbers: 81% wealth increase for billionaires since March 2020 (adjusted for inflation).

Accelerator B: Profit concentration (market power, global players)

Large, scalable companies were often better able to absorb crises: supply chain power, pricing leeway, digital sales channels. The markups debate (IMF/OECD) fits here as structural background.

Accelerator C: AI and tech valuation boom

Oxfam explicitly points out that the development of AI‑related stocks (and political frameworks) has given additional tailwind to super‑rich investments.

6) Germany as an example: How the trend feels locally

In its German analysis, Oxfam also shows the “turbo at the top”:

- The number of billionaires in Germany is said to have risen to 172 in 2025 (one third more).

- The total wealth of German billionaires is, adjusted for inflation, 840.2 billion US dollars (plus 30% in 2025).

- At the same time: a significant share of the population lives in poverty (Oxfam speaks of about one fifth).

This is a pattern that can be found in many countries: at the top, wealth rises at crisis speed, at the bottom, life becomes more expensive and insecure.

7) The core of the classification: 50 years, one common thread

If you wanted to boil down the last 50 years into one formula, it would be this:

We have built a system in which capital (ownership) structurally grows faster than labor (wages) – and in which political rules often reinforce this effect rather than brake it.

The Oxfam figure “+81% since 2020” feels like a scandal of the present. Historically, it is more the moment when a long-term development visibly explodes.

Because since the 1970s, several gears have been turning at the same time:

- Taxes: less progression at the top (OECD).

- Labor power: weaker unions and collective bargaining coverage (OECD).

- Distribution: productivity decouples from typical compensation (EPI).

- Market structure: more market power, higher markups (IMF/OECD).

- Financial logic: asset booms act like wealth levers (BoE/QE).

- Tech/globalization: scaling and financial integration reinforce winner dynamics (IMF).

The result is an economy that not only makes people rich at the top, but reproduces wealth.

8) What can be taken from this (without moralizing)

- The “80% since 2020” is not an outlier, but an acceleration of half a century.

- The question is not whether billionaires “may” exist, but why the rules of the game let wealth grow so much faster than income.

- If wealth generates political power, then inequality is not just a social problem, but a problem for democracy and governance – and that is exactly what Oxfam is targeting in its current report.