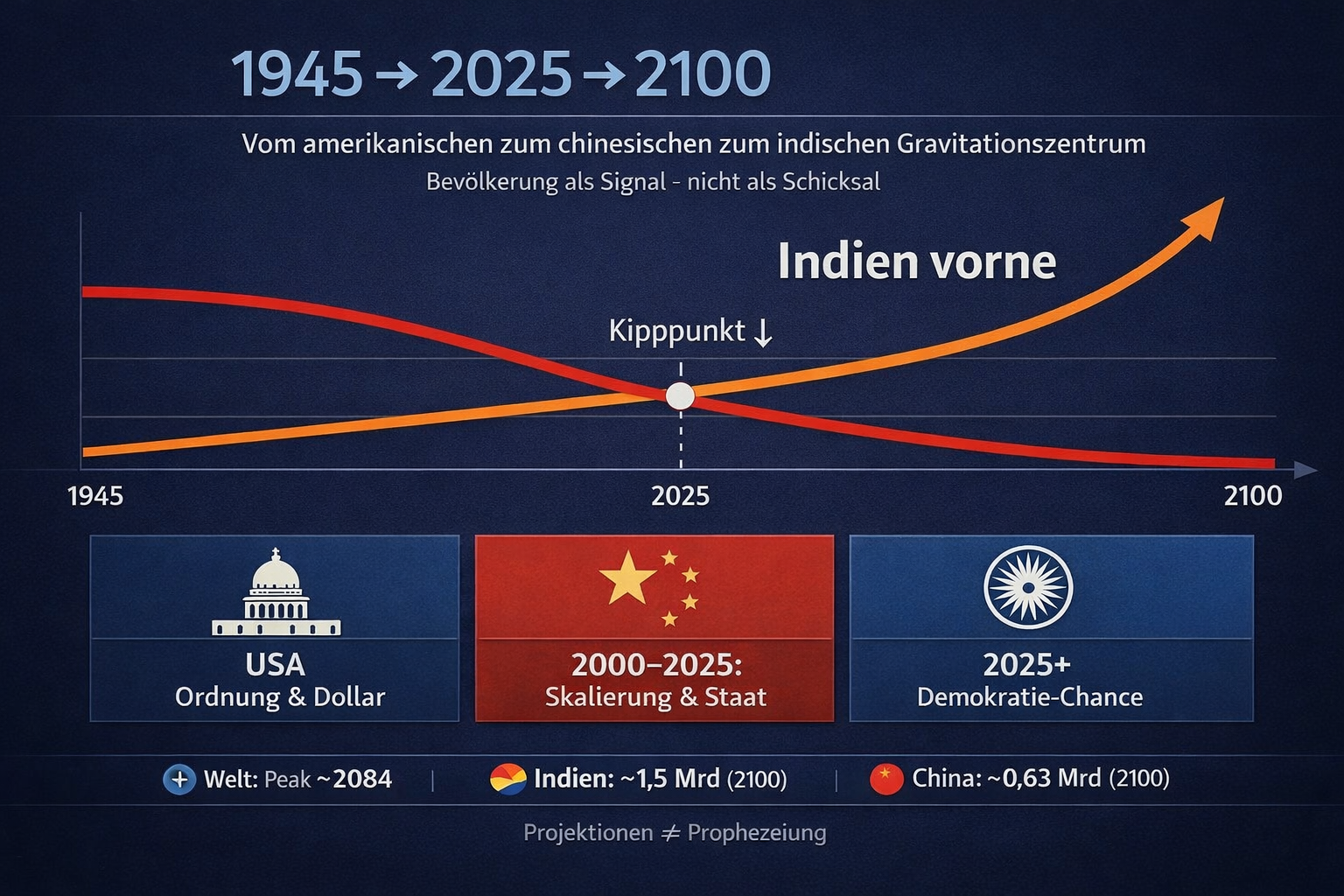

1945 → 2025 → 2100 – From American to Chinese to Indian center of gravity

My statistician’s heart laughs. Not because “more people” would be good per se (it is not automatically), but because there are these rare moments when a sober curve suddenly writes history. Such a moment is the tipping point at which India has overtaken China as the most populous country – the UN dates this change to April 2023.

And yes: In the year 2025 there are roughly 50–60 million more Indians than Chinese – an order of magnitude you cannot talk away. This is not “a bit of statistics”. This is an entire country of difference.

1) The number is the hook – but not the story

The short version of the curves (rounded so we don’t pretend these are natural constants):

- 2000: China ~1.26 bn, India ~1.06 bn.

- 2020: both ~1.4 bn, China still slightly ahead (back then the race was already practically decided).

- 2023: crown change – India takes over.

- 2025: China continues to shrink; the official figures show a renewed decrease in 2025 (4th year in a row), to around 1.405 bn.

Now the important classification: population is potential, not automatically dominance.

It is raw material: labor, market size, tax base, soldiers in an emergency, talent pool, consumers, voters (in the democratic case). But raw material has to be processed – through institutions, education, infrastructure, capital, energy, legal certainty, technology. Otherwise potential becomes a burden.

And this is exactly where the big arc begins.

2) 1945: America’s century – order & dollar

If you take 1945 as a starting mark, then not out of nostalgia, but because from there a world order emerges that still has an effect today:

- The USA leave the Second World War as an industrial, financial and military great power (and – more importantly – as a rule‑setter).

- The dollar becomes the global reserve currency; international institutions, alliances and security architectures stabilize this status.

- The “American center of gravity” is not only economic power, but a complete package: capital market, military, innovation, pop culture, universities, networks.

This is the first principle: power = system + trust + infrastructure (not just tanks, not just GDP).

The punchline is uncomfortable: even those who are “against America” often still move within the American system – because the system was (and in parts is) the cheapest, deepest, most liquid, safest standard option. This inertia is a superpower in itself.

3) 2000–2025: China’s moment – scaling & state

Then comes the second act: China.

I would describe it like this: scaling as statecraft.

China has – over decades – achieved something that is rarely seen at this speed: gigantic industrialization, export dominance, infrastructure boom, technology transfer, and increasingly its own tech capacities. That was not “the market will take care of it”. That was “the state organizes it”.

And now what happens is what many (including me) underestimate: demography does not simply turn slowly – it tips.

China has had a shrinking population since 2022, and 2025 was already the fourth year in a row with a decline.

This is not a footnote. This is a structural headwind on three levels:

- Labor market: fewer young workers, rising labor costs, more pressure for automation.

- Welfare state/aging: more pensioners, more care, fewer contributors.

- Growth model: when the domestic market ages and shrinks, “simply selling more” becomes more difficult – and more politically risky.

China remains a heavyweight – but the direction is new: from growth to managing maturity. That is a different game.

4) 2025: India’s tipping point – democracy opportunity (with tough conditions)

And now India.

This is the moment when my statistician’s heart briefly cheers – and my realist immediately clears his throat behind it. Because India’s overtaking is symbolic and strategic, but not automatically “India wins”.

What is really relevant about it?

- India is now not only “huge”, but permanently the largest talent pool.

- India is not just “cheap labor”, but (potentially) the largest demand machine: consumers, middle class, digital services, mobility, energy, infrastructure.

- India is – at its core – a democracy: change of power through elections, party pluralism, public debate. This is slow, chaotic, sometimes exasperating – but it is a different mechanism of legitimacy than one‑party states.

The “democracy opportunity” is:

If India translates the demographic potential into education, jobs, productivity and institutions, then this is a gain in power with a different political DNA.

And yes, I consider that – normatively – to be good: a world in which not exclusively authoritarian state models or oligarchic duopolies set the pace would probably be more robust. (Probably. Not guaranteed.)

But (and this is the decisive but):

India has to pull off the trick that many countries with a “young population” have missed: demographic dividend instead of demographic burden.

This is not a feel‑good mantra, this is mathematics:

- If millions of young people do not find productive jobs, it becomes politically explosive.

- If infrastructure, energy and housing do not keep pace, urbanization eats up quality of life.

- If education and health do not scale, productivity remains low – and then “more population” brings headlines but no dominance.

India has the opportunity. But it also has the duty to execute.

5) 2100: projections ≠ prophecy – but they are a damn loud warning

Now the leap that hurts in the head: 2100.

The UN projections (WPP 2024) say:

- The world population will continue to grow for a few more decades and will reach its peak in the mid‑2080s at around 10.3 billion – in analyses 2084 is often mentioned as the peak year.

- After that it remains roughly stable or falls slightly towards 2100.

For the two giants this means (also UN projections, rough order of magnitude):

- India: continues to grow for a few more decades, peak around ~2060 at ~1.7 bn, and is at ~1.5 bn in 2100.

- China: shrinks significantly and is at ~0.63 bn in 2100.

This is not “a bit less”. This is a halving. And this is the reason why this article is not a party‑hat contribution, but a geopolitics wake‑up call.

Because: demography shifts gravity.

Not automatically dominance, but gravity.

6) From the “American” to the “Chinese” to the “Indian” center of gravity – what does that mean concretely?

When I say “center of gravity”, I do not mean “who is morally better”. I mean:

- Where are the largest markets located?

- Where does the largest share of new workers and consumers arise?

- Where is production, where is investment, where are standards set (tech, climate, data, trade)?

- Who has bargaining power because others are dependent (supply chains, raw materials, security, capital)?

1945 it was the American center: dollar, rules, alliances, institutions.

2000–2025 it was (and is) China’s center: production, infrastructure, supply‑chain dominance, the state as scaling machine.

2025+ could become India’s center: people, market, digital scaling, geopolitical swing player.

“Could”, mind you. In capital letters.

7) Democracy vs. one‑party state vs. two‑party machine – my (deliberately provocative) point

In my original text I call the USA a “2‑party dictatorship” and China a “1‑party dictatorship”. That is pointed – and yes, it is meant to sting.

What is my real point?

- China: one‑party state, high steering capacity, little political competition, strong control over the public sphere.

- USA: formal democracy, but structurally an extremely polarized two‑party system in which “election” is often experienced as a binary identity decision – with all the side effects (populism, gridlock, culture war).

- India: democracy with gigantic diversity, federal complexity, and a political competition that sometimes produces more volume than governance – but which also has corrective mechanisms (elections, courts, public sphere).

My desired image is not “India will solve everything”.

My desired image is: more real alternatives, more checks & balances, more competition of ideas – and less compulsion to sort into “us versus them”.

Or put differently: if the 21st century is going to be multipolar anyway, I would prefer that one relevant pole is a democracy (with all its flaws) rather than a model that cannot correct mistakes without losing face.

8) “And what if China were not America’s biggest creditor?” – small reality check (that does not destroy the punchline)

In my original text there is the idea: financial dependence tames political escalation.

That is not wrong. But the specific formulation “China is the biggest creditor” is no longer precise today.

According to U.S. Treasury data, Japan is currently the largest foreign holder of US Treasuries; China is behind it (and has reduced its holdings in recent years).

The punchline still stands – just formulated more cleanly:

- China is (still) a very large creditor/investor in US government bonds, and this interdependence is part of mutual deterrence.

- At the same time, this very table shows how the power picture is shifting: not just “China vs USA”, but a network of holders (Japan, UK, financial centers, funds) that co‑finance American deficits.

What would a (random) US president do if this interdependence did not exist?

Probably take more risks. Not because “evil”, but because costs later and voter benefit now are a dangerous combination.

(And yes: that is exactly why it is so disheartening when politics becomes reality‑TV logic.)

9) What does this mean for Europe/Germany? (Because otherwise we just watch)

If I take the arc 1945–2025–2100 seriously, then a fairly unromantic to‑do follows for us:

- Understand India as a strategic partner – not as an “outsourcing address” or “emerging market”.

- Diversify without moralizing: supply chains, technology standards, energy partnerships.

- Talent and education: whoever wants to win the coming decades competes for minds – not for the best Sunday speech.

- Democracy return: if we see democracy as an advantage, we also have to make it capable of delivering (infrastructure, digitalization, administration). Otherwise it is just branding.

10) Conclusion: my statistician’s heart laughs – but it does not clap blindly

The tipping point “India overtakes China” is real.

China’s shrinking is real.

The 2100 projections are a loud structural announcement.

Whether this becomes an “Indian age” is not decided by the birth rate alone, but by the ability to turn demography into productivity – and power into legitimate, correctable order.

If India succeeds in this, then (yes) I look forward to this world.

And if not, the curve still shows mercilessly: we do not live in an eternal present. The center of gravity is shifting. And we should stop being surprised.

😉